A bread without salt and a new translation of the Paradiso

If you haven’t yet read the Divine Comedy you know who you are—now is the time, because Robert and Jean Hollander have just completed a beautiful translation of the astonishing fourteenth-century poem. The Hollanders’ Inferno was published in 2000, their Purgatorio in 2003. Now their Paradiso is out. Jean Hollander, a poet, was in charge of the verse; Robert Hollander, her husband, oversaw its accuracy. The notes are by Robert, who is a Dante scholar and a professor emeritus at Princeton, where he taught the Divine Comedy for forty-two years.

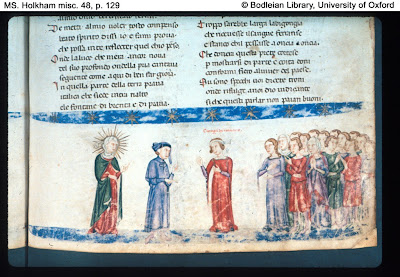

The entire Comedy is an allegory, a symbolic representation of the highly systematized theology that St. Thomas Aquinas and other Scholastic philosophers distilled from the Bible, the Church Fathers, and Aristotle in the late Middle Ages. But in the Paradiso the allegory is far more naked than in the Inferno or the Purgatorio. In Dante’s time, and for a few centuries afterward, readers of poetry (learned people, mostly priests) were accustomed to allegory, and thought it was a good teaching tool, because it made you work. As Boccaccio said in his “Life of Dante” (1374), “Everything that is acquired with toil has more sweetness in it.” But since the early eighteenth century that is, since Europeans began questioning the faith that is Dante’s subject there has been a tradition of discussing the Comedy in terms of a “duality” between its allegory and its “poetry.” What is suggested here is that the allegory is anti-poetical, and that what is acquired with toil is mostly toil. The best-known modern statement of this position is a 1921 book, “The Poetry of Dante,” by the philosopher Benedetto Croce. The allegory that is so great a part of the Divine Comedy, Croce declares, is non-poesia, “not poetry,” and he makes fun of it.Croce’s book fell like a bomb on the Italian literary world Luigi Pirandello wrote a wrathful review of it and still today it is regarded by some as an irresponsible document.

When he wrote the Divine Comedy, Dante, because his political party had been routed, was in exile from his native city, Florence, and was living with friends, sometimes in Verona, sometimes in Romagna or Ravenna. The Comedy takes place in 1300, two years before he was expelled from Florence, but in Heaven his great-great-grandfather Cacciaguida predicts his banishment: he will learn how salty is another man’s bread, Cacciaguida says, and how hard it is to go up and down another man’s staircase. What could be simpler or more concrete than this a staircase that seems long, bread that tastes peculiar? (Hollander informs us that, to this day, Florentine bakers make their bread without salt.) Critics exclaim over how much of our world there is in the supposedly otherworldly Comedy. In Paradise, there’s less of it, but it’s still there. Snow falls; the sun burns off the morning mist. Clocks chime (the first reference in European literature to mechanical timepieces). Babies nurse; pigs and dogs do what they do. A pilgrim arrives at a shrine the place he has vowed to travel to and greedily stares here and there in the church, knowing that the minute he gets home his neighbors are going to want to know everything. This last is more than an image; it’s a little story.(much more from New Yorker by Joan Acocella )

I have read parts of The Divine Comedy, Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso and blogged on the trip to Florence that was dedicated to it. http://www.sherrilsmyriadofmusings.blogspot.com/ - 9/9/07

ReplyDeleteWhere is Ein Hod? I will come visit on my next trip to Israel.

Sherril

ein hod is an art village 15 km south of Haifa

ReplyDeletei have links on the blog to ein hod site

zeno